16/09/2021

Dialogue 7:

Helena Winkelman & Alina Petrova

"What I need to do is to allow my body, my intuition as a player, my sense of sacred things to go into the music directly without putting a lot of obstacles in the way"

The guest of this issue is a violinist, composer and the artistic director of Camerata Variabile Basel Helena Winkelman. The interviewer is a performer, curator and the founder and a soloist of the Kymatic ensemble Alina Petrova.

More about participants

Stravinsky's Dialogues: Helena Winkelman & Alina Petrova

Обработка видео...

— Helena, hello. My name is Alina, I’m from Moscow and I was asked to interview you and maybe partly also because… Well I made my thanks for the guys for inviting me but I think, I’m assuming that I was invited to interview you because I’m myself an instrumentalist. I play the viola, I finished the conservatory as a viola player. And I have my own project which is the ensemble for contemporary music, Kymatic ensemble which performs a lot of different contemporary music with an accent on composers that are… so to say non-institutionalized composers. So musicians that are… so to say like in-between, like experimental, popular, noise, ambient music. Working with instrumental setups, lineups. And I write music myself, I compose music myself. So, well, I could maybe call myself a composer, but I’m a little bit shy of saying that. And I would actually would like… this could become maybe one of the topics. I was very pleased, it was very nice to get acquainted with your work. To be honest, I will be honest that I didn’t know your music. And I think in this relation it is a very good thing because I have very quite a fresh view on the theme. And maybe I could, I’m able to formulate questions that a person who doesn’t know you well… So in this interview could be maybe a bit more accessible for the wider audience in this case. And I think it could be correct to ask you the first question concerning your biography, your life. And I think it makes sense to touch it from the instrumental perspective, so to say. So because you were a violinist. So can you talk, say a couple of words of this experience, of yourself as a violinist? Where did you study, how it just happened that you became a performer, and what now is happening in this field of your life?

— Yes, gladly. In a way I have to smile at your word “were” a violinist, because I still very much am a violinist. So I’m still performing a lot, I have my own mixed chamber group in Basel where I also make all the programs. And I also still practice all the sonatas and partitas by Bach and I also perform them in cycles occasionally, it’s my favorite music. Anyway. And I write a lot for the violin evidently. Also these works I play in public. So the playing for me still is of the same importance as the writing. And that’s also very important for my work. Because only writing on a desk without a direct experience of what it means actually to perform, for me is just very incomplete. And if you look back into the past, all great composers have also been excellent performers. It’s very normal.

So I have actually my maybe most intense connection with Russia actually comes from two and a half years of studying in Mannheim with Valery Gradov. He’s a Russian violin professor who also taught Frank Peter Zimmermann. And after that time that was very intense, I really was inspired, became soloist and I realized something in my life was missing. And that was the creative part. So I went for one year to New York to discover new areas. And I always knew there was something more than to play the violin in my life. But there I realized it was composition. And then I went totally into composition. I wrote nine hours a day trying to find my own language.

— Can I ask you when the turning point for you to be thinking that you need this… When did you have this urge to have the creative bit? Can you remember this moment, the turning point? To creativity as well.

— Yes. There is actually such a turning point. I mean… But the roots were laid much earlier. I had when I was younger a violin teacher. Which means improvisation from a very early age on. So I was always improvising, without any fears, without any, you know, usual trepidations which classical musicians have. Normally they don’t like to come on stage and just play what comes to their mind. And for me that was very easy. But actual writing down of music I had obstacles because I felt I never knew enough about music theory.

And then when I started to study music, actually violin, in Lucerne, first of all I ran into one of the greatest improvisers of our country who was percussionist, Pierre Favre. From him I learned a lot about what is music behind the notes. And then also in that time I for the first time heard Bartok’s Second String Quartet. And there I suddenly knew, here I can start to continue from. But still, you know, I was then 18 or something, and I felt I first had to try in my body to the best extent to become a really good performer. So it was kind of too early, I wrote some really small pieces but nothing of real, like, enduring value.

And I first had to go to Mannheim to study violin, to finish my studies, which I also then continued a little bit in Basel later. But actually the composing only started when I was in New York. Because there also I found some teachers, I took some classes in Juilliard with Stanley Wolfe. And I also met Philip Lasser who was an exponent of the Nadia Boulanger school, the French school, who was very heavily into counterpoint and harmony. And let’s say all or many American composers and also film composers were kind of brought forward by her school in the long run.

— Do you remember your first piece that you have ever written? For what instrument it was written and what was the form and genre of the piece? So was it a big piece or a small piece, what was the first piece that you remember?

— My first piece which is not out there anymore it’s called Triceratops and it was for violin solo and it was about a dinosaur. And I actually wrote it for my eleven-year younger brother who also was a violin student.

— How old were you when you wrote it? Just to understand.

— 18 I was.

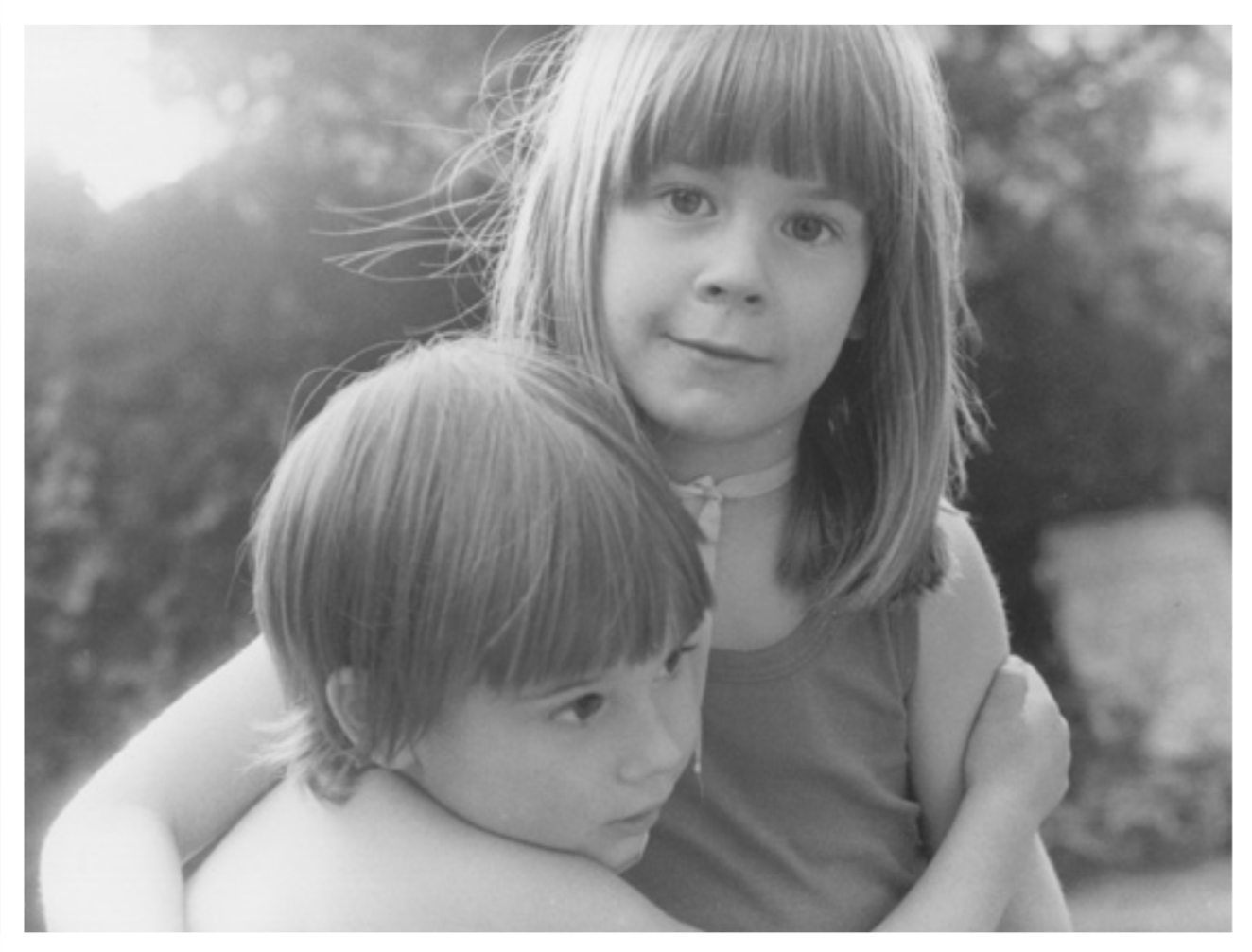

Helena and her brother Florian at childhood

— Yeah, so this is kind of the start, to understand the starting point. It is interesting that when a performer starts writing pieces, writing music, I don’t know how it happened with you, but I know it by my own experience that there is inattention and… So there is this world of composers very well formed and quite, it seems, quite a closed world of people writing music. So what was the first, which step should be first take so that you’re… So, for example, if we see a situation, there is a performer who wants to become a composer, what suggestions or advice would you give making first steps into writing music? What would you recommend to such a performer?

— I think especially if one is already an adult, what in my eyes is very important to find back a kind of child innocence of playing. In a way you know you don’t want to criticize yourself too much. It’s like with a child you don’t say, “Don’t do this, don’t do that. No, that’s wrong, no, no that’s bad.” You carefully do it.

And sometimes it helps actually to improvise first or look for new ideas on an instrument that is not your own. I had a long talk once with Sofia Gubaidulina and she told me about a beautiful experience on actually improvising with friends on instruments she didn’t know at all. She said it was very liberating.

And then of course what I also did in the beginning I recorded sometimes because the part of writing down is time-taking. And sometimes the flow of the music can be hindered by the writing process. So one needs to become very comfortable with writing first and very comfortable of being in the flow of the music second. Both instincts ideally are here. And then what one can start to do is think of music, think of motifs, think of melodies and then start notate immediately.

And what I do often to avoid writer’s block, I go with a small notebook to the park and I write down everything that comes to my mind. Just short motifs. Sometimes on one tree, I need something to write against, I use a tree, and then I walk to the next tree and I write the next motif on the next tree. No judgement at all. And I come home and my whole book is full with motifs. And then, after I sit on the piano, and I start actually putting harmony to the rhythmical and melodic little fragments. So these fragments become like personalities. They have already their own mood, they have their own thing which they want to say.

And then the next step in actually writing the composition is like, I feel like a king anyway. You are master of life and death when you are a writer, when you are a composer. You can actually do what you want. But if you want to be a good king you have to look at your subjects. You have to say, “This guy is very intelligent. He should do this. This guy is very strong, he should do that. This motif is good to open. This motif is good to close. This motif asks for an evolution.” And then you see what are the qualities of your subjects, of your kingdom. And then you know where in the compositoric structure put your subjects. And from this you can start to build the big structure.

What for me is very important to make this a cohesive whole thing is to actually have ideas about the piece before I start to look for motifs, before I go for walks. So of course I know, for example, for which instruments I am going to write, is it going to be choir, is it going to be orchestra. This is one narrowing down.

And Stravinsky said if he’s too free when he writes, it’s not going well for him, he needs restrictions. So what kind of restrictions do I give myself? That’s the big question. And the restrictions for some composers come by, for example, using the twelve-tone system or by using serialist ideas. For me it was never like this. For me it always came from the thing I want to express. I have, for example, I see an atmosphere. I only have to look at the clouds and I see a certain atmosphere. My mind projects itself onto the clouds. And this gives me feeling inside and I say, “This feeling is represented exactly by this chord. Only this chord in this spacing can represent this feeling.” So I have invented something new. But not from a serialist idea, but from an internal, expressionist idea. And this helps me to make every piece I create a completely different thing. I never have to copy myself.

Of course I have certain things my ear just likes. I like spectral chords, I’m just crazy for them, I can’t help it. And I think also for a composer it’s very important to follow his love. So you should write what you love to hear. In this I am totally biased. I will never try to be objective, I just say, “I love this, I love this, I use this to say that.” Which also means that because I’m led by my love or things that I can integrate a lot of different cultures into my music, a lot of different styles, without actually having it be a patchwork. It becomes a patchwork if you just use it like in a little box, like children put a horse here, a little gem here, another thing they like here. It’s not like that. Because if you love something really very much you take it inside. And inside it starts to actually digest itself and put it together with other things that you love. So it takes time, this thing. It’s not like you can do it instantaneously and it’s not being made here. It’s something that happens in the heart.

Helena Winkelman spielt Jürg Wyttenbach: A tragedy (a ballad for singing violinist)

Обработка видео...

— This is a very very interesting thing inside which I have a lot of questions that I want to ask you now spontaneously. The questions that were not planned. So I will start maybe from the slightly… I haven’t seen the scores unfortunately. I would love to see the scores but they were not available unfortunately to me. And so the creative process is very interesting, this was the most important question that I wanted to ask. Do I understand correctly that you have this notebook where you’re writing motifs, then you come home and you work them, you kind of continue working on them? So are you using any… Have you ever worked with field recordings of some sort? Do you use them in writing your music, do you use sounds and sentences, or synthesizers, or electronic ways of dealing with sound is not your thing, or only acoustic or instrumental things are important to you? So what do you think about all these things? What do you have to say?

— Principally I am very open. I mean I appreciate artists a lot who are doing this. I’ve done this myself very rarely. I’ve once actually worked on a piece of music on something we have particularly in Switzerland which is called Suonen. And in the high mountains usually the earth for peasants is very dry, it doesn’t give enough water to plant crops or anything. So they built long long long sides of the water along the sides of the mountains. From the glacier came the water and it came along these waterlines which are really built… Many people lost their lives, it’s very dangerous to do that. And there is water in these lines. You know, sometimes from boots, sometimes from stone. And this water makes a certain sound. And I wrote a piece about this. So I went with my father and recorded different sounds of water. And then I wrote a piece for four flutes that was kind of interlacing with the sound of this water, imitating how the water sounds. That was the one thing I was working with samples.

And in another very early big ensemble piece I actually worked with the old Odyssey, which is one of the first synthesizers. You know, where you still have to work with wave generators then all these curves and stuff. And I loved these old instruments because they’re so unpredictable. They… You have to really work with your intuition to find what you want. So this I like.

— Do I understand correctly that often the recorded sound becomes an inspiration for you to create something new in more of an acoustic or… It’s not being taken as a separate instrument? So you are being inspired by the recording, an instrument, sort of orchestrated for the instrument? So it becomes an impression rather than another tool to use?

— Well, the recording is still present. I mean, you will hear the water for example in this flute piece. It’s absolutely there as a sound. And also the Odyssey evidently is an instrument that is on stage that is being played live during the performance. So it’s not just an inspiration. But what I do is of course I try to integrate it into the rest of the piece. So I don’t just keep it as an object but I keep it actually as something to make a very close relationship with, with the other instruments.

— So you said that you started writing actively when you moved to New York which I wanted to ask you. Was there a principal difference in the way the composition is taught in Europe and in the United States?

— You know, that’s a very difficult question to answer. Because I think even in Europe there’s not one homogenous way of teaching composition. I know that when I returned to the Academy in Basel to actually start composition with Roland Moser and after what’s also with Georg Friedrich Haas of course I was more exposed to, let’s say, this European idea of looking at composition. And I think the way how we compose for many years was of course influenced by the Second World War. And in a way I also felt that musicians try desperately to write music that was not able to be abused by dictators.

I mean I have been translating the reviews Steve Reich got on his first tour to Germany after the war. This was like in the late 60s. And I remember some of the reviewers writing, “Oh my god, this music is dangerous, it induces some kinds of states in the mind that are not safe, that are… One should stay away from.” And other listeners were so glad to get out of this harsh serialistic stuff. They’ve had so enough of it. So it was a very divided way of receiving this music by Reich. And I mean I’m not a minimalist at all. But I just find it interesting to observe what’s going on in the mind of the culturally attentive, the historically attentive crowds that actually say: “We had a problem with a huge dictator that was using some kind of mass hypnosis on us and made us do all kinds of atrocious things. So we have to be careful that music doesn’t kind of go into that direction.” And nowadays obviously music has become politically completely irrelevant. Also partially because we chose to be. I say, music in a way has become completely politically irrelevant, I say. And it also because we chose to be.

— Yes, so I understood that this is quite a complicated question whether there is this difference. But it’s interesting… So how it helped still… this education in the United States helped you or gave you some additional maybe tools, maybe some preferences… No, sort of additional compositional tools in comparison with people who studied for example only…

— Okay. Yes. I understand. I mean, of course what is a huge influence or was a huge influence in New York, first of all, jazz. I went to a lot of jazz sessions, all the free jazz and all kinds of experimental things. And then also of course I felt that the American approach to dissonance is a completely different one than in Europe. I mean, at least, let’s say, I’m not speaking about now some specialists which of course also existed in the States. But generally I feel that my ear when I was in America was more influenced by jazz than by anything else.

And I also felt in the music I wrote shortly thereafter, I actually found a rock group made out of nine strings, percussion and piano. And I really tried to bring together the popular music and the, let’s say, Western classical contemporary music. And that was a very daring thing to do at the time. I mean, many people commented on it, saying, “Look, you really fall between the chairs here because it’s neither contemporary music nor is it really jazz, so what are you trying to do?” And now, twenty years later, everybody moves into that direction. So I was just a bit too early with this idea.

And also what was very good in the United States is that I felt, you know, all this huge obligation towards all great geniuses of the past. It was just not so strong there. There was more space to experiment, more space to fail. And of course if you start as an 18-, 19-year-old, you know what failure is. You know you have a high intention, you have high aspiration, you know what you want to get from it. Your ear is cooled by all these great masterworks. And you write something and you go through it and you realize it’s not on that level. It’s pretty painful.

— And this is also an interesting question. If I understand correctly, so you had a very, quite a few composers teaching you, that you took classes from. And this is interesting… Could I ask you to maybe talk about each of them and maybe just say shortly how they… So what part of them has transferred into your composition world? What reflected the most?

— Yes. Okay. So obviously the first one, Pierre Favre, this percussionist… You know his very very great particular personal strength was that he was regarding rhythm as a melody. And I would say a lot of the power my music has actually comes from the rhythm and how I deal with rhythm. And that rhythm for me is a very physical thing. So I think towards rhythm not as an intellectual but I think it with my body. And I think that comes from Pierre a lot. And he also made me realize that it’s a great beauty movement. That movement has its own organic strength. Sometimes you make a movement for a certain while, for a certain time, and suddenly you feel now it’s enough. For example, as a composer intellectually if I think okay, I wanna do 64 bars of polymetrics because I calculated it, I think it’s good. But after 32 bars my body says, it’s enough, stop. And if I overrule my body and go with what I’ve calculated, unfortunately the listener doesn’t know what I calculated, he hears with his body. So the problem is I should listen to my body to not hurt the listener’s body. This is a direct non-verbal communication. Music is non-verbal communication. And this I learned from Pierre. This is very big, that is most profound influence.

And afterwards when I went to America I met Philip Lasser. And here I learned a lot of… And I mean he is quite an important composition teacher. He was the youngest composition teacher ever in Juilliard and now he’s teaching in Harvard. And he had a lot of pride in music theory and in musical theoretical findings. And from him I learned that these things can be nice and important. And also how to analyze Bach. And you know, about inside counterpoint, if you have only one line how do you make a counterpoint.

And after this I went to Basel and I met Roland Moser. And he is the guy I studied with for four years. This is my official formal composition studies. And he’s now… He was there in his last five years of teaching. He was a very experienced guy with a fantastically refined reflection on music and on craft. I mean, the amount of fine thinking, literary thinking, poetic thinking, his way of dealing with text, everything, he’s like for me close to ideal.

And he’s also very close to György Kurtág who is one of my other very big influences, he’s the famous Hungarian composer, you know? This guy. He’s now 95 and he lives in Budapest. They are still very much in contact. So he never was teaching composition, Kurtag. But Moser’s work in many ways has many resemblances to the ones of Kurtag. In some ways it’s also very different. But they understand each other very well and yeah… The history evidently is different, and their characters are different, and you hear that in that music. But in sense of aesthetics and in sense of just cultural depth that is behind writing these two are very close. And Moser really… When I came from America to him my scores were like jazz scores. They were very empty. I just wrote notes and the rhythms and I expected the interprets to do the rest themselves. So he taught me to be very very precise, in articulation, in all the dynamics, in everything you need to communicate to the interpret.

— What do you think is there a person in the world right now, maybe a composer, a musician or… who you would like to still maybe study with? If there is such a person who you would love to maybe take something from? Or to talk to. Who would that be?

— I mean, Kurtag of course is there. I mean, although he never teaches composition I know I can ask him if I want to know something. The other person I really really appreciate, on whose work I also have done my thesis when I did my composition diploma is George Benjamin in London. I also was allowed to sit in into some of his classes when he was teaching in King’s College. And for me he’s also unbelievably refined, spiritant . What he does so well is to distinguish between foreground and background. Especially in his operas. You know, his singers are never crowded by the orchestra. There’s always space, and his space is luminous and beautiful.

Helena Winkelman "The Clock" Merel Quartet

Обработка видео...

The Clock

— Another question. I will start from far away. What do you think about tonality? What is tonality to you? Does it… So is there a place for tonal music in the 21st century, what do you think, what is your opinion?

— That’s a funny question. I mean, I know that like 20 years ago or 30 years ago this would have been a very sensitive issue to speak about. But nowadays we have such a diverse contemporary music world that in a way for me that question is pretty… Almost unnecessary. Because… I mean, I remember when I was in a music academy and I wrote this jazz duo, Rondo with a Janus-head (Rondo mit einem Januskopf) for violin and cello. I really felt like a strange dog in the academic consensus of how contemporary music sounded, you know. And what for me is important is that the music is vital. And of course old music came from dance, and dance has a certain rhythm that’s also harmonical rhythm. There’s opening, closure, the whole chording, everything you want to express. And then of course you had a side of tonal music was that you especially in church wanted to help people feel what actually is written in the sacred texts. So you wanted to make the sacred texts not only in the intellectual game, but you wanted it to be felt with the heart. And for this harmony is very very important. And I think human beings don’t do very well when they don’t live from their heart. We have a tendency to be a little bit intellectual nowadays. It’s like almost a sign of nobility to be an intellectual. But for me it’s… These things need to be brought together I think and no other thing can do this as well as music.

— So you would say that your music… Would you say that your music is partially tonal? Or it’s not partially tonal but it’s tonal. What would you… How would you describe it?

— Well, the thing is I try not conscientiously to avoid function harmony. But it’s kind of not so interesting to me. I know that spectralism for me is where I first time started to understand music theory. Because spectralism is something where I viscerally felt in my system, in my physical system, this is right, this sounds right. And we also have in Switzerland all these big instruments like alphorn that work with these microtones that come from the overtone series. And of course from my teacher Georg Friedrich Haas I learned a lot about other microtonal systems. So microtones I use very easily. And then of course microtones open the entire world between the notes. Which anyway is out of function harmony. And then, you know, what also with Haas I learned is about how terribly attractive it is if things have slow evolutions also with slow glissandos and suddenly you lose the ground under your feet and you’re in a kind of open space where you do not know how to orientate.

— And what do you listen to yourself when you’re not working?

— (laugh)

— Because maybe you don’t listen to any music, you get too tired…

— Actually I mean a lot of music I listen to is actually also… Because I study something, because at the moment now I’ve just finished a big sextet for percussion called Goblins. And for this subject of course I was researching what goblins are and they have a very big interest in it for example in Korea. And in Korea they are having this pansori, this kind of storytelling with only one drum and one singer. And these drum cycles from the pansori they have been recorded, you can find them on Spotify, they can also be played on the V-Drums and with several drums and these cycles are so intricate and so beautiful. So I was trying to learn from them for my piece.

— Spotify was very recently allowed into Russia and I myself started listening to a lot of music just as background. And I just… So I listen to noise, to electronic music. And there are a lot of them on Spotify. And they are in playlists. Spotify suggests you a lot of different performers. When you read their bios, they are called composers. Still they don’t have any classical education. So they are intuitively feeling their style and they’re writing music in their own way. And very rarely they take classes of trained composers or getting any additional compositional education. What do you think, as a person who is… So you had a lot of different experience with a lot of different composers, with different educations. And you spent a lot of time in the academic world, especially as a violinist. So what do you think about that? So who can be called a contemporary composer now and should they get this academic experience, academic education, apart from maybe the tools they are already using intuitively or they know intuitively or they already use for doing what they already can do and like?

— First of all, who am I to say what’s right and what’s not? I think if one is seriously and passionately interested in a thing one wants to do, evidently every human being will try to find input, will try to find help, will try to find ways to become the best it can be. And obviously our society gives chance to young people or also older people nowadays to enter a context where growing kind of is really encouraging every possible way. And for this I think academies are not so bad. I mean there’s many people who are trying to do the same thing as you, who you can talk with, you can have actually a lot of private time with a teacher for comparatively little money. So in many ways an academy is an ideal growing place if you can handle it.

The good thing for me was when I was entering the academy as a young composer is that I have already written quite a lot of music. I already had my own aesthetic. If you go there not knowing at all what you want and basically you want people to tell you what you should do, don’t go.

— I give lessons myself sometimes. And sometimes people who write music come to me. And they are writing music in all those well-known programs. They ask me a lot and I want to ask you. Why do you think notation, so writing music through notes, still exists? When a lot of people can create it virtually. And another question is how notation helps you connect your mind and your thought to bringing it to life, to the performance? What is the magic in-between? Why do you need to write notes?

— Well, that’s the thing. Notation I think was mainly developed for coordination purposes. I mean if one could make music just as a single person, then it’s easier. I studied also quite a lot of Indian music. And for example like for centuries Indian music has not been notated. But still it’s one of the most highly developed musical cultures there is on this planet. But the way they did is in a way they use improvisation based on certain agreements, on certain pre-meditated or practiced, for many years practiced structures. So in a way in the moment you access things that are rooted in your system and everybody taking part in, the group musician taking part in the playing knows that same system. So there you don’t have a problem with communication. And there’s a strictness to it but also a lot of liberty. That’s the beauty. If it comes…

Yeah, to Western European music it’s more complicated. Let’s say you cannot get together with a string quartet and read Haydn if you cannot read. And if Haydn would not have written it down we wouldn’t even be able to access this music. So in a way I think writing down is a selfless act because it gives you a chance to give away the music you wrote to other performers. And for this also in a way I like the writing process and I do it with a lot of love because it’s for me a way to tell someone else what I’m feeling. When I work with a good interpret, especially, it’s almost like I design a beautiful journey for him. Or I know this person does this, and this, and this very well or this person sound in this register so beautiful or this singer is especially good at this. And then I write particularly for this person. And because I write with notation which this person can read, it’s quite, let’s say, 80% of things I can actually communicate.

— If to analyze, notation for you as a composer, is it blocking you? Or is it help or is it an obstacle that you need to overcome?

— Let’s say it’s both. Let’s assume I only have a four-track recorder. And I’m just basically improvising one line above another. You can say it’s easy pickings because I write my first line, this line is as this. And I record a second line, maybe I have to try three or four times until it sounds good, I do the third line, maybe I have to try three or four times until it’s really fitting. And you can say, okay, I’ve created a piece in half an hour. But the thing is where the writing helps. Is that you actually can experiment with a bigger structure. Which I find is difficult. Because writing allows you to go forward and backward in time. Because there’s a visual element to it.

Actually played music goes just forward in time. And in a way our consciousness goes in cycles. If you see somebody who is a good speaker, he speaks about the subject. He says it’s about this. He explains a bit, he says again it’s about this. He explains a bit, he again says it’s about this and now we understand why it is about this, because I told you this and this. And this kind of structure is not happening so easily. I mean to improvise it well you need tremendous schooling like the Indian musicians have for example. And as a composer, when you write down, it’s a bit easier because you can write down your main subject. You can try to write transitions. You can metamorphize your subject because you have written this other part. And you can have things changed and actually you can work on things just on a much more profound way if you notate. That’s what I want to say.

— So can you please think of yourself ten years ago? What would you say changed, what principally changed for you as a composer? In those last ten years.

— I would say that in the last ten years my writing has become even more intuitive. I almost never calculate anymore. In all when I came from the academy I did a lot of superstructures, I did a lot of intellectual things because I kind of felt I needed to do that to be a good composer. And I realized now actually it’s the opposite. What I need to do is to allow my body, my intuition as a player, my sense of sacred things, all the spiritual things I’ve experienced in my life to go into the music directly without putting a lot of obstacles in the way which is just calculations and plays games of materials and stuff. I love the materials and I never make them cheap, I make them very beautiful and as intricate as I can. But they are not my supergod, you know. The content is what’s important.

Helena Winkelman "Zauber - und Bannsprüche aus alter Zeit / Spells and charms from ancient times"

Обработка видео...

«Заклинания и чары из древних времен»

— What advice would you give to young composers who are starting writing music? This is maybe for me mostly now because I myself need a feedback when I show people what I do. I’m myself in a situation now as a composer that I have a lot of formalism. So structures and compositional methods they are very important and I’m working on a material thing but it should be very very strictly structured because a composer is a person who is doing that well basically, who is combining materials very nicely. And I understand that I’m not alone in this, that maybe everybody comes with this period. What maybe advice could you give to a starting young composer?

— First of all, I can only in a way pass on what my Indian singing teacher told me once I asked him for advice. And he just looked at me and he said, “Feel more.” Then it’s one side. But then the other side of course is, if one starts to create structures, one has to always ask oneself, is this structure which I’ve just created actually representing what I feel? Is it connected? Because otherwise it will be empty. And there’s so much empty noise in this world, it’s better to be silent actually. But if one really really has to say something, if it’s profound, everybody will be glad to listen. Because there’s so many people who feel a lot which they don’t know how to express. And I think composing for me is not only like writing a diary. It’s also not only about myself, it’s about finding something that’s profound enough which is of course subjective, it can be subjective. But that other people can identify with it. I always… I love to tell this story about Sting, you know. When his father died, he had a huge crisis with writing. And then he went back to his home town and there, most of the people there were shipbuilders, it was somewhere in North England. And he realized suddenly that these people needed a voice. You know, to express themselves, to have the world realize they exist. And how life is there. And we all in a way feel caught up in our own heads and fragmented in a society like we don’t belong or we don’t know who we belong to. And if somebody else who comes from somewhere completely different, who had a different life, manages to tell us how they feel and how their life is, we are just a little bit less lonely.

I mean, for example, it would be for me totally not correct to write rap. Because I’m just lacking the background. And also you know, for me it’s also in a way fake if I would write this kind of strict serialistic in a way very often unemotional music or let’s say music that was trying to distance itself from direct emotion because of what happened during the Second World War. I haven’t been in this war, I haven’t experienced it, I’m a different generation. I want to be honest. But I still insist on saying that I think it’s very important if one is creatively busy with something, it can also be a painter or a writer, not only composers. I think it has a great therapeutic effect to write diaries. But I think our job is not doing this. We have to do it for other people too.

— Yes, I understand. You said about rap. And I have a spontaneous question. Okay, do you listen to rap?

— Yeah, you know I mention this because I actually listen to such huge amount of different music, I’ve even once been to a Slayer concert. Because I wanted to feel this dark metal or metal atmosphere. And it actually was quite an amazing experience for me, I really liked it. Because it was so focused, you know, people were so there. But at the same time I must say with rap I have a problem. I mean I understand that it comes from wonderful oral culture where politics and rhythm has been combined to make an impact, that actually you are really working in a very strong way politically when you do rap. But the whole kind of culture behind it and the images behind it… It just doesn’t appeal to me at all, it’s not my piece of cake. I’m just differently. And so I don’t force myself to listen to it. I mean I was a great fan of Phil Collins and I’ve recently been to concert of his where his son was playing the drums and he’s now 18-19 and he did an incredible job. And it was just a wonderful experience, I went there with my father. I listen to a lot of pop music. I also went to a concert with Tina Turner, with David Bowie, with Michael Jackson, even in the 90s. I know all these old guys and you know, there is, in the collective we have nowadays, there’s a certain fascination to this monster concert with 25000 people. And because something happens in the atmosphere. Like people come together in a way that is very beautiful and makes me personally less scared of these big collectives. And I think that’s one of the jobs of music too. But rap essentially no, I don’t connect to it at all. No.

— I listened to your piece for two violins and orchestra with you and Patricia Kopatchinskaja and in connection with this I wanted to ask, what recollections do you have of the joint, work in joint music playing or performance? Are there any things that you could share about that?

— First of all, I mean, actually the piece was written for her and Pekka Kuusisto, the Finnish violinist. And he couldn’t come to play so I basically was jumping in. And I have fantastic memories of working with the orchestra and Patricia. We had a lot of fun. It was really one of the good moments of my life.

— Are there any interesting stories that you could maybe share of this interaction with Patricia?

— Well, the thing is, you know, what I heard before I started working on this piece is that she and Pekka tried to play a string quartet and that they ran a little bit into troubles. I mean they are both very very strong characters. So I as a side interest or let’s say… I would never say a hobby because it’s much too serious, I’m interested in all kinds of psychological studies, I have also done hypnotherapy or how do you say, education, I’ve done a lot of shamanic training. And in a way I always try to see the bigger picture if I enter a project. And I had a kind of intention of writing a piece that after this piece Pekka and Patricia would be really, have a really good time and kind of forget all the difficult things and that they really love each other after playing this piece. So that was kind of secret intention of that piece. It was a little bit like, I wanted to be a little bit like a relationship therapist with this piece. And that’s also how the piece is built, you know. Usually when two people are in trouble you say, okay, look at it from a little bit of a distance. And it’s gonna be much easier. So the first three parts are basically all about the universe. And also about this double sun system that exists. You know, where two stars are rotating around one another. Very beautiful to look at actually if you have a chance. And then the second part is basically first a little drunken waltz which could not be performed as recorded because the piece has become too long…

And if it’s drunk then suddenly you know the three becomes a little bit tum tsa tum tsa tum tsa tsa tsa um tsa tsa because it can’t walk straight, you see? Hee hee. And then after this there is a little scene where we almost put our heads together and played by memory. It’s very intimate. And then there is a scene called parallel parking which in a way is very… almost… I mean with the rhythm and everything It’s very sexual. And then there is also a scene before that with birds where the two violinists are like birds sitting on little tweets, singing to one another. So it’s also like we humans, you know, we have our relationships but we’re also part of a much bigger picture. We have all this energy in us and we have a huge universe around us and all our problems are not so big in the end, no? And in the last movement actually the two violinists, they gang up to sink the orchestra. And sink in sense of make it drown. And the way how I did this as a composer is I had the two soloists play very difficult phrases, more and more difficult phrases and the orchestra had to imitate. And at one point of course they would fail.

— That’s interesting. In connection with what did you study shamanic practices?

— Yes, I mean I know that obviously in Russia there’s a lot of traditions also still <…>. But I don’t know the Russian tradition so well, I’ve mainly studied in England with a guy who studied in North America for 25 years. But there’s of course some core shamanic things which are the same in all cultures, no matter if you are in Russia or Korea or North America. It’s the same, it works the same way.

— The question, for what purpose did you study it?

— Oh, for what purpose… First of all, because I just wanted to become a better musician. And also because I’ve had some serious health problems at one point which I needed to find a solution for. These two things. And you know that was an old time I think when let’s say the medicine people in a village they were the musicians, they were also dancers, they were storytellers, they were healers, they did everything.

— What experience did you take… So what knowledge did help you personally and with composition when you studied those practices?

— I think the first thing of all is connecting with something that is sacred. I think that was there already before. But it was kind of formalizing a little bit, it gave practices and tools how to connect with it. And it also helped me much better to trust my intuition, it helped me balance certain aspects of my life. I mean as artists we sometimes tend to become a little bit extreme in one side or extreme in another side. And there’s a lot of old teachings that tell you how to in different situations bring forward different parts of yourself so you can navigate well. And for me that was important. Also conflict resolution. Like working with groups and people, there’s always conflicts and always difficulties.

— In the previous question we touched the aspect of… You mentioned that there’s a lot of sort of informational noise, there are a lot of things around us and a lot of different information. How do you deal with that?

— I think anyway we all filter information according to what we need. And I think what helps me the most is to start day with very clear questions: what do I want to do, what do I want to experience, what do I want to see or hear today. If I don’t have these questions, it’s overwhelming. It’s like calibrating the filters.

— Have you ever experienced a crisis as an artist?

— I had two big crises in my life, one physical, one emotional. Because I had a brother who died early. But strangely enough the writing wasn’t stopped by it. Actually I must say that my writing almost became better. Yeah.

— So you didn’t have situations when you didn’t know where to go as an artist? So this never happened to you?

— Well, I had times where I just was not motivated. Like, let’s say from last October until this May. I just felt I needed a break. I was looking to a lot of Korean dramas, I was just allowing myself not to write. Because before I wrote like every year about one hour and fifteen minutes of music, every year the same. And I said okay, I’m not a machine, I don’t want to. And evidently I couldn’t finish a trumpet concerto which I should have, I was late, I am now late with a lot of other things. But I’m not beating myself up. I just say okay, it’s how it is. And yeah, sure, it had to do a bit <with> the lockdown, you know, this entire covid thing, not knowing when things can be performed again and also not seeing my wonderful performing friends. It was very hard on me, it’s being so alone, I’m a very social composer in that sense.

— Yes also I wanted to ask you how you lived through the covid when all the things were… Everything was closed. So we had a year off all things. This probably was a very complicated time for you.

— Yeah. I mean thank god financially I did not have too many worries. That was kind on the safe side. I spent a lot of time with my father and my parents in general. I was in touch with a lot of old professors in a way I haven’t been before. And I’ve just realized how much love and affection there is. And also to cultivate these relationships was so important. In that sense covid was a real good thing for me. So that I didn’t see so many people, but the ones I saw it was more profound. And I also did some recordings of my old teacher’s works which I was very happy with. And of course I mean I’m not very proud of having watched so many Korean dramas. But some of them are actually pretty good. And I learned a lot about acting. I was not somebody who went to the theater a lot when I was young. And some of these actors are really good. So that was helpful to me. And if I ever write, you know, for a movie, let’s say a film soundtrack, or if I ever write for more for the theater I think I’m in a better position now.

— Did you have any commissions of writing music, writing film music?

— For film music no. Actually I’m totally virgin [laughs]. But you know, I think this is a very particular field in some way which has a lot of people already working there with a lot of experience. So like with any field you have to get into it and you have to make the first experiences. I know that Schnittke, for example, he has written a lot of film music and he considered his film music as important as his other music. And the problem of course is for me also when I was working on my first opera in Buenos Aires or with other music for theater is that you’re not completely in control of the situation. It’s always the director of the film who tells you how can be. And sometimes you need to cut, you need to throw away things or rewrite things very quickly. And that needs totally different way of working.

— So the question is, is composition a competitive field in general?

— Well, you know, the thing is I’m somebody who does not give the best work when I’m feeling competitive. There are some people who are running up to very great performances when they are competitive like runners or even instrumentalists. But for me it’s not like this. I’m more of a lonely discoverer who must have the feeling that I’m entering a territory where there was no one before. And in a way with composition because every composer is so different and every composer has such an own voice, this is very easy for me. I mean evidently for performers it’s also like this. Great performers are so different, like different fruits. One is like that and the other one is like this, they get different energies even if they play the same piece. And every of these energies is beautiful and you want it to exist. So even in this there’s not a real competition. But in a composition actually I don’t feel it at all. And I try to support other young composers with my group, we try to perform pieces. We… yeah. For me it’s about such a much bigger thing than competition and the composition.

— And the last question that I want to ask. What are your future plans?

— I want to marry next year [laughs]. No, no. No, I have to write a bassoon quintet which is for the bassoonist of my group here in Basel and quartet of Ilya Gringolts so it’s a very excellently beautiful group and I’m very happy. And then the next thing I have to write is trumpet concerto and then I’m writing a kind of crossover project with people from the jazz school here in Basel and from the old music department in Basel. So I’m trying to make a piece called Minimal Minima which is like probably the most minimal music I’ve ever wrote for this group which is very rhythmical and very fun. It’s supposed to be like 20 minutes. And then I’m also going to write music for a puppet theater for the Franz ensemble. It is a German group, mixed group. We usually play Schubert’s Octet and now I’m investigating in all Grillparzer and all these writers from the Biedermeier time around Schubert’s time to see if I find some interesting plots for this.

— Thank you very much. We are wrapping up. It was a very interesting discussion. And thank you for your honest answers to my questions. And I think that thanks to this interview people who listen to your music, it would be more clear maybe to them. But thanks. To me it became definitely more clear. And I think I understood a bit more now about you and your music.

— Thank you Alina. It was very nice to talk to you. I wish you all the best with the composing and let me hear it sometimes.